Sayama end of Siboma

Ombonara end of Siboma

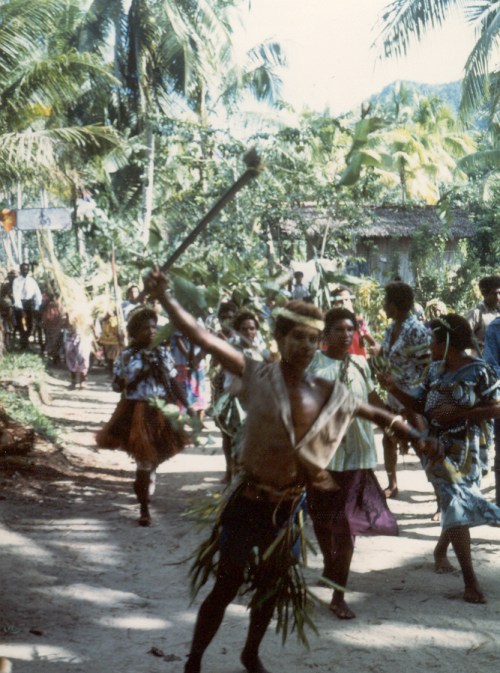

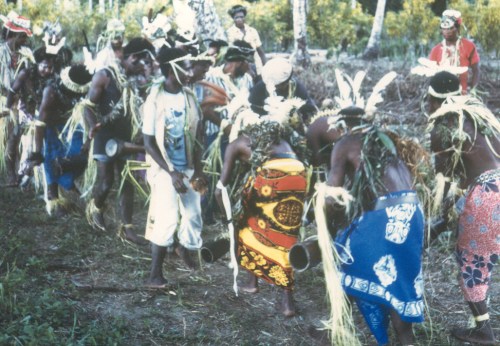

On the way back from the 1976 Sam, young men and women from the Numbami delegation performed their Singsing Baruga at Kela village (called Manindala in the Kala language), with whom the Siboma villagers had helped sponsor delegates. Here are a few photos from that performance.

Tilapa woya baluga. Titabinga ata.

Tilapa woya baluga. Titabinga ata.

Kolapa luwa tisipi sa ambamba

Ekapa to kolapa tilapa woya baluga

Young man enters wielding war club.

Young man enters wielding war club

Bumewe ilapa ambamba ipandalowa ima

Kolapa tilapa ambamba tipandalowa tima

Kolapa tikarati wai woyama inggo inalapa woya baluga

Tilapa woya baluga. Kolapa teulu tidudunga.

Kolapa titota ata ditako. Kole te inumu yabokole

One side of Siboma village in 1976

Siboma village, 1976

Siboma council house and central plaza

Daniel Siga’s lumana (bachelor quarters) and beachfront

Siboma village house under construction

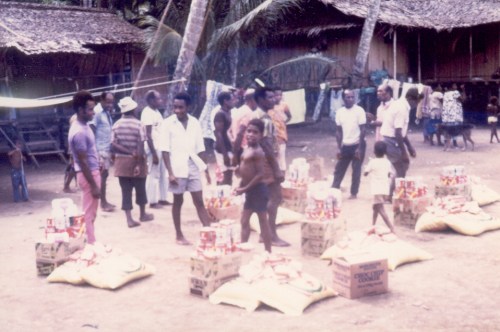

Allocating goods for a village party

The following story is one I translated from the Jabêm-language Buku Sêsamŋa II [Book for reading, 2nd ed.], by Rev. M. Lechner and Nêdeclabu Male (Madang: Lutheran Mission Press, 1955), pp. 10-11:

Mec bôc kê-tôp-ŋa

magic pig 3sR-grow-for

Magic to grow pigsLau Sibôma sêsôm mec teŋ kêpi soŋgaluc

people Siboma they-say magic one it-upon pufferfish

Siboma people say a kind of magic on the pufferfishma sêsôm teŋ kêpi m

and they-say one it-upon banana

and they say one on the bananagebe bôc têtôp ŋajam.

say pig they-grow good

so that pigs grow well.Sêsôm kêpi soŋgaluc

they-say it-upon pufferfish

They say it on the pufferfishgebe i tonaŋ embe daŋguŋ nga sao êndu

say fish that if we-spear with fishspear dead

because when we spear that fish deadma têtacwalô êsung êtu kapôêŋ sebeŋ

and its-belly it-swell it-turn large fast

then its belly will swell up big quicklyma bôc êtôp êtôm i tonaŋ

and pig it-grow it-match fish that

then the pig will grow like that fishtêtac kêsuŋ kêtu kapôêŋ sebeŋ naŋ.

its-belly it-swell it-turn big quick REL

whose belly swells up big quickly.Ma sêsôm mec teŋ kêpi m

and they-say magic one it-upon banana

And they say magic on the bananaŋam gebe bôc êtôp êtôm m,

reason say pig it-grow it-match banana

so that the pig will grow like the banana,naŋ tasê kêsêp kôm

that we-plant it-into garden

that we plant in the gardenma kêpi ŋadambê kapôêŋ me gêuc sebeŋ

and it-rise trunk large or it-stand.upright quick

and its trunk grows or stands upright quicklye ŋanô kêsa ma kêtu lêwê,

until fruit it-rise and it-turn ripe,

until its fruit appears and turns ripe,ma bôc êtop sebeŋ amboac tonaŋgeŋ.

and pig it-grow quick like that-Adv

then the pig will grow quickly in the same way.

Filed under history, reading/writing

Genitival modifiers in Numbami, an Austronesian language of Morobe Province, Papua New Guinea, may either precede or follow their head nouns. This word order difference has consistent semantic correlates. For convenience, I will refer to the Modifier + Head genitive order as the “possessive” genitive. This contrasts with the “attributive” genitive, which has Head + Modifier order.

There are two types of genitives with Modifier + Head order. One is simply a noun-noun compound without any intervening markers of a genitive relationship. Such compounds express whole-part relationships. The modifier indicates the type of larger entity of which the principal entity (that denoted by the head noun) is a part. This modifier is descriptive rather than referential. There are no restrictions on the referentiality of the compound as a whole. It can be nonspecific—that is, it can denote some not-yet-uniquely-identifiable member(s) or quantity of the set it describes. It can be generic—that is, it can refer to any and all members (or the entire quantity) of the set it describes. Or it can be specific—that is, it can refer to some individually identifiable subset of the set it names. Because the term “generic” is sometimes used in both the nonspecific and the generic sense (as just defined), it will be convenient to use different terminology in the discussion that follows. The term “attributive” (or “nonreferential”) will substitute for “nonspecific” and the term “referential” will take the place of both “generic” and “specific”. Examples of whole-part genitives in Numbami follow.

In contrast to the modifiers in whole-part genitives, those in possessive genitives must be referential. The reference of the head noun is also restricted. It must be referential.

The possessive genitive is the only type in which the modifiers may be pronominal. The internal structure of the majority of genitive pronouns parallels that of the genitive nominals. The independent pronoun appears in the same position as other nominals.

| Pronouns | Pronominal genitives |

| woya | na-ŋgi kapala ‘my house’ |

| aiya | a-na-mi kapala ‘your (sg) house’ |

| e | e-na kapala ‘his/her/its house’ |

| i | i-na-mi kapala ‘our (excl) house’ |

| aita | aita-ndi kapala ‘our (incl) house’ |

| amu | amu-ndi kapala ‘your (pl) house’ |

| ai | ai-ndi kapala ‘their house’ |

The preposed genitive is also the only way to express a possessive relationship between personal possessors and inalienable possessions. Remnants of former suffixed possessives show up in the middle of a few body-part and kin-term compounds, however. Only the kin-term infixes show agreement with the preposed pronouns, and then only with the singular pronouns.

Noun-noun possessive constructions are distinguished from noun-noun (whole-part) compounds by morphology as well as by semantics. Singular possessors are indicated by na and plural possessors by ndi. One of these two morphemes intervenes between the preposed referential genitive modifier and the head noun.

There are two types of simple attributive constructions with Head + Modifier order. Noun-adjective constructions are one type. In Numbami they contain no markers of a genitive relationship. The adjectives themselves are attributive rather than referential, and the construction as a whole may be either attributive or referential.

While adjectives carry no morphological indication of an attributive or genitive relationship, attributive nominals are marked as genitive. They are followed by either na or ndi. Singular na is far more frequent. Plural ndi is only used when the attributive nominal denotes a type of people with whom the referent of the head noun is characteristically associated. Attributive nominals never refer to a particular subset within the set they name. Instead, they only restrict reference to a subset of the prototype set denoted by the head noun. The construction as a whole may be referential or attributive, but the modifying nominal is nonreferential.

The attributive genitive seems very close in meaning to the possessive genitive when the reference of the construction as a whole is generic (as earlier defined). Both bani bumewe ndi ‘European food’ and bumewe ndi bani ‘the Europeans’ food (the food of Europeans as a “genus”), can refer to the same set of food. But the difference is this: The attributive nominal helps identify the referent by subtyping the head noun according to its association with another type of entity. The possessive nominal helps identify the referent by associating the head noun with another referent. Possessive genitives, in fact, are as much a means of referring to possessors as they are of referring to possessions. The following example illustrates.

Kundu, ena lau wa kapole, ena wambala tiyamama

sago its leaf and leafstalk its cargo all

nomba sesemi. Sese ena bolo luwa.

thing one&same but its skin two

‘Sago, its leaf and stalk, all its content is the same. But its husk is of two kinds.’

The semantics of the attributive genitive, on the other hand, make it suitable for other functions. Since it identifies entities by subclassifying them, it is useful in distinguishing homophonous or polysemous words and in creating new classes of entities.

Neologisms and periphrastic translations of foreign terms are frequently attributive genitives. The head noun denotes a familiar general prototype and the genitive identifies some familiar domain with which the new entity is associated. The attributive genitive construction thus characterizes the novel entity by creating a novel association between familiar entities. This is the point at which genitive constructions shade into relative constructions.

Filed under grammar

The following story was told to me in 1976 by a Numbami man who was a noted traveler and storyteller whose nickname was “Samarai,” because he had once spent time there. (My late West Virginia uncle had also spent time as an Army cook on nearby Goodenough Island after spending time in Australia. He had a lot of respect for the Aussies, and he’d been in fistfights with more than a few of them.)

In this first, rough translation, I’ve tried to capture the storyteller’s idiom without presuming too much specialized knowledge on the part of my readers. We can be sure the story has “improved” over countless retellings, but it nevertheless conveys a third-party perspective on the Pacific War that is too rarely heard. For more local reactions to the Pacific War, consult the Australian-Japan Research Project for Australia and PNG, and the book Typhoon of War for Micronesia.

While were were in school [around March 1942], the Japanese came and took over Lae, took over the Bukaua coast [the south coast of the Huon Peninsula], all the way to Finschhafen. But we stayed there at school for another year. Then, okay, the Australians and Americans seemed to be planning to come back. Their number one patrol officer, Taylor, sent a letter saying, “Natives, don’t stay in your villages any more. Build huts in your hillside gardens and stay there. A big fight is coming.”

So here’s what we did. We people at Hopoi abandoned Hopoi. We took our school, our desks, and everything and set them up in the forest. We stayed at a place called “Apo.” We kept going to school and, okay, the Australians came from over on the Moresby side, they came all the way to Wau. And they came down that little trail and they and the Japanese fought each other over at Mubo and Komiatam [above Salamaua].

And they sent word to us Kembula [Paiawa], Numbami [Siboma], and Ya [Kela] villagers to go carry their cargo to Komiatam. And they did that and the fighting got harder. The Australian forces got bigger. And some Numbami went and carried cargo over at Salamaua. They went at night. They went there and the Australians came down and fired on the Japanese so the Numbami ran into the forest.

They ran into the forest and there was one guy named G. “G, where are you? We’re leaving!”

So, okay, they went and slept overnight and the next morning arrived at Buansing. And a Japanese bigman there named Nokomura [probably Nakamura], he heard the story so he came down and talked to me. He talked to me and I said, “Oh, that was my cousin, my real [cross-]cousin.”

So the Japanese guy said, “Really? Your cousin? Oh, your cousin has died. The Australians shot him dead.” And he spoke Japanese, and he said, “One man, bumbumbumbumbumbu, boi i dai.”

I said, “Oh, you’re talking bad talk.”

Then he said, “Tomorrow, you go to school until 12 o’clock, then come to me.” So I went to school until 12 o’clock and I went to him.

He gave me, dakine, a rifle, a gun. And he gave me, dakine, ten cartridges, ten rounds. Then he said, “I’d like for you to take this and go shoot a few birds and bring them back for me to eat.”

So, okay, I took it and I went. And he wrote out my pass. And there were bigmen with long swords the Japanese called “kempesi” [probably kempeitai, the dreaded military police]. One man, his name was Masuda [possibly Matsuda]. This man had gone to school over in Germany. And he really knew German well.

So I came by and he saw me, “You, where are you going with that gun?”

So I said, “Oh, a bigman gave it to me to shoot birds for him to eat.”

“Let me see your papers.”

So I showed him my papers and he said, “Okay, go.”

So I went and found a friend of mine. His name was Tudi. I said, “Hey, Tudi. A bigman gave me a gun and I haven’t shot a bird yet. Could we both go and you shoot?”

“Okay.”

So we both went and stopped at an onzali tree and two hornbills were there. So he went and planted his knee and shot one and it fell down. So I was really happy and ran and got it. We kept going until he shot a cockatoo.

So after I thanked him, I said, “Give me the gun and I’ll see if I can shoot.”

So he gave it to me and we kept going until we saw some wala birds, and I said, “I’ll try to shoot. Shall I shoot or not?”

So, okay, I fired and I shot a wala bird to add to the others. So I said, “Okay, we have enough, so I’ll take it and go.”

So I tied the wings together and hung them over the gun and carried them back over to Buansing. I went and all the Japanese bigmen were sitting in a, dakine, committee. They were talking about the coming battles. They were sitting there talking and their bigman said, “Look, here comes my man,” and the guards saluted him. And I was invited in.

So I entered the building and the guard at the door said, “Ha!” When he said that I replied, “Ha!” And I bowed three times and he bowed three times.

After we finished, okay, I went up to the second guard and he went, “Ha!” And I said “Ha!” And I bowed three times and he bowed three times. Okay, then I walked on.

So then I went up to the man who stood at the steps up to the bigman. When he said, “Ha!” then I said, “Ha!” and we had both bowed the third time, I went up the steps.

I went up the ladder and the people who were sitting in the meeting, they stood up and went “Ha!” to me and I said “Ha!”, then I went up and they gave me a chair. I sat down.

And the bigman glanced at his cook. And, okay, he took smokes and opened a pack and passed them around until they were gone. Okay, then he struck his lighter and gave everyone a light, then we all sat down. We sat and sat, maybe a half-hour. Then he told his people, “Okay, the talk is over.”

So they all split up and went out leaving just him and me still sitting. We stayed sitting until he said, “I’ve already given you a blanket and a mosquito net. Here’s a knife. Here’s your lavalava. Over there are your bags of rice and dried bonito, two tins of meat, a tin of fish.”

I said, “Oh, you’ve given me so much. How will I carry it?”

He said, “Oh, it’s all right. Take it away.”

So I asked him, “You’ve given away so much. What does it mean?”

“Oh, there’s a reason. I guess I’ll tell you. After you leave, a ship will come tonight, a submarine will come and I’ll board it and go to Rabaul.”

I said, “Why are you going to do that?”

“Nothing. All us bigmen are going up to Rabaul because the bigmen and a whole lot of soldiers are at Rabaul. And these people, their job is to stay behind, and fight the Australians and Americans when they come, and destroy them, destroy them here. And us bigmen will be in Rabaul.”

“Oh, all right.”

Then he told me, he said, “You go get a good night’s sleep so that when you see the crack of dawn you’ll get up quickly.”

Listen to the fuller story in Numbami here:

The following story was told to me in 1976 by a Numbami man who was a noted traveler and storyteller whose nickname was “Samarai,” because he had once spent time there.

In this rough translation, I’ve tried to capture the storyteller’s idiom without presuming too much specialized knowledge on the part of my readers. We can be sure the story has “improved” over countless retellings, but it nevertheless conveys a third-party perspective on the Pacific War that is too rarely heard. For more local reactions to the Pacific War in Papua New Guina, consult the Australian-Japan Research Project.

We went and slept until the first crack of dawn when it was my time to sound reveille. So I went and struck the, dakine, slitgong: “Kuing, kuing, kuing, kuing, kuing.” So then the boys woke up and bathed and washed their faces. When they finished, okay, the bell rang.

The bell rang and all the people went to school and were singing. As soon as they finished, I ran right up behind the school and stood atop a rock.

When I looked out, I could see as far as the Huon Gulf and, okay, it was completely dark.

I said, “Hey guys, come look at something. The boys said, “What is it?”

“Come look!” And when they looked, “Guys, let’s scatter!”

Okay, they went and gathered up their things and fled into the forest. Before we left, the guns started sounding, “Bum, bum, bum.” They were firing at the soldiers at Singkau and Kabwum and Lae and Salamaua. You could see fire and smoke all over the place.

Okay, all the Bukawa and Hopoi people went into the forest. I ran to my house and roasted some taro cakes under a tree. I planned to take two to eat in the forest.

I was doing that and our teacher Gidisai and his wife and kids came up. And just then a crazy Japanese man came up. He had no gun, no knife, just walking around empty-handed.

“E, Kapten!”

So I said, “What?”

“E, Kapten, Japan boi hangre, ya.”

“Oh, I don’t have any food.”

“A, banana sabis [= ‘free’], ya? Japan boi hangre, ya.”

The teacher said, “Are you crazy or what? You go fight!”

“O, nogat [= ‘no’], ya. Japan boi sik na hangre, ya.”

“Oh.” I heard that so I stayed and thought, “Oh, if he stays there, the guns will kill our teacher for sure.” So I stood by and didn’t go into the forest.

I was standing there waiting and, suddenly, “Japan boi, yu mekim wanem [= ‘you do what’]?”

“Boi, hangre, a, imo [= ‘tuber’] sabis, ya? Imo sabis?”

“O, imo planti planti istap faia [= ‘are on the fire’]. Olgeta sabis [= ‘all free’]! Kam kaikai [= ‘come eat’]!

He went and sat down and ate taro and I said to the teacher, “You all go quickly!”

So they ran way over into the forest and hid themselves in the rocks. And then I said, “Japan boi! Yu kaikai. Yu stap. Yu slip haus. Mi go.”

“Mm.”

Okay. I took my things and ran into the forest.

Listen to the fuller story in Numbami here:

Numbami words < likely Guhu-Samane sources

abo ‘goodbye’ < abo ‘goodbye’, aipo ‘leavetaking’

abuabu ‘mud, muddy’ < qapu ‘clay pot, saucepan’

ausama ‘warclub’ < usama ‘wooden fighting club’

egaŋaiŋai ‘wallaby’ < eka gahigahi ‘wallaby’

eloma ‘amethystine python’ < eromara ‘snake type’

gaiboli ‘echidna’ < gaipori ‘echidna’

gaweta ‘emerald monitor lizard’ < kabesa ‘small green lizard’

geleŋgau ‘tree frog’ < kerengau ‘type of frog’

gobe ‘rat, mouse’ < gope ‘rat, mouse’

ibaluwa ‘tree kangaroo’ < iparuba ‘tree kangaroo’

kaebe ‘sugar glider’ < khaebe ‘sugar glider’

misimisi ‘sandflea’ < misimisi ‘mosquito’

siliwo ‘ground skink’ < siriquba ‘smaller lizards, geckos, chameleon’

suni ‘small bat’ < suni ‘bird type’

ubela ‘gecko type’ < (q)upera ‘gecko’

ubu ‘pandanus type’ < upu ‘inedible pandanus type’

zimani ‘acorn’ < ttimani ‘oak with edible acorns’

zole ‘termite’ < tore ‘termite, white ant’

Filed under vocabulary